by Mahmud Rahman

When I visited Dhaka last August, a street art panel on Road 16 in Dhanmondi caught my eye. Right next to the entrance to Sunbeam’s School, it had an image of tea being poured from a kettle and the words, Eikhane Rajnitir Alap Nishiddhyo, with Nishiddhyo crossed out and replaced with Joruri. Translation: Political Discussions Here Are Prohibited, with Prohibited crossed out and replaced with Urgent.

I assume this panel was painted during the summer of 2024 when a mass upheaval shook Dhaka and Bangladesh, beginning with public university students, spreading to private university students, school children, workers and other young people. A movement that began with demands to change the quota system in place for public jobs faced ruthless suppression and galvanized into a movement that ousted Sheikh Hasina’s fascist regime.

Some critics of the movement have suggested that the joining of the movement by school children, street kids, and others without any stake in the quota movement signified that this was not a natural explosion but a ‘meticulously designed conspiracy’ by agents of the CIA or other intelligence agencies. They slander the movement as a ‘color revolution,’ a concept that’s become popular among some to suggest movements against tyrants aren’t legitimate but engineered by great power machinations.

How else, why else, they ask, will young children join such movements?

I want to take you back to 1968-69, during the movement in then East Pakistan that overthrew Field Marshall Ayub Khan, when some of us, barely in our teens, me fifteen, my comrades even younger—all of us school children, and not just any schoolchildren but from one of the so-called elite schools in Dhaka—became animated by that movement.

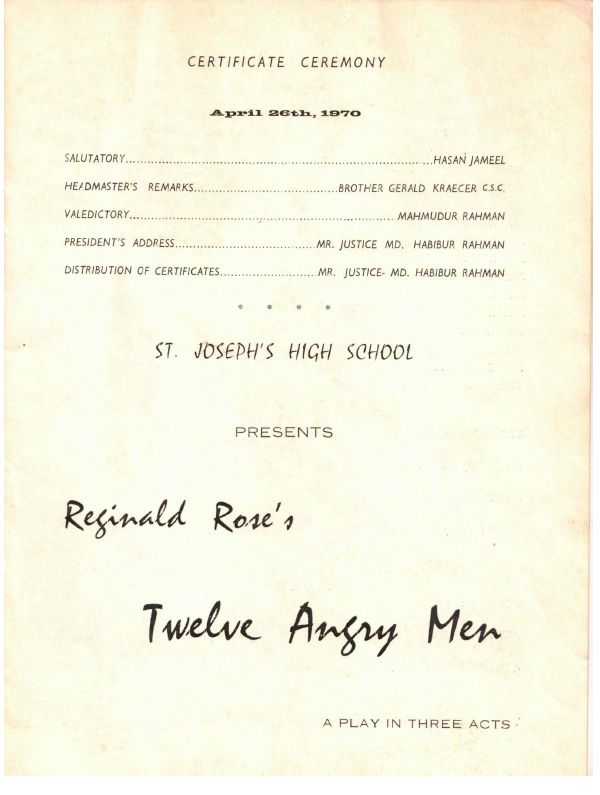

In 1969 I was a student in Class Ten at St Joseph’s High School in Mohammadpur. I was one of those known as ‘good students,’ doing well in schoolwork and active in science club, debates and theater, the Interact Club. I also produced the school newspaper, The Sentinel, cranking it out on a mimeograph machine.

Even among the Catholic missionary schools, St Joseph’s was an elite school. Unlike St Gregory’s, it only offered English medium instruction, and while the tuition at St Gregory’s was 25 rupees a month, it was 40 at St Joseph’s. The school-end exams were not the Dacca board SSC (‘matric’) exams but the O Level GCE from Cambridge University. I would have gone to St Gregory’s where my brothers went, but there had been no available seats when I needed to enroll in Class Four.

In our school, there were many more students of West Pakistani background, the sons of businessmen, military officers, government officials. Bengali students were more middle class; they included children of businessmen and some government officials but most had parents who were professionals. My father, a retired police sub-inspector, made his income through renting out storefronts.

My class was preparing to sit for the O Level exams that year and most were preoccupied with schoolwork, sports, or other extracurricular activities. But we knew what was happening around us; the sand was shifting beneath our feet. In the center of the city, university students had begun rallying in the streets against Ayub Khan. One January day, the police shot and killed Asad, a student leader. Hartals were declared and Ayub Gate, an ornamental arch on the main road near our school was renamed Asad Gate.

St Joseph’s was quiet. One day during a hartal to protest another police killing, some university students led by Sheikh Kamal, the son of opposition leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman who was still in prison, dropped in with a few of his comrades, shouted slogans in the corridors, and encouraged us to leave our classrooms. We were eager enough to protest and some of us took out a small procession that marched down to Asad Gate.

A few of us began attending student rallies at Bot Tola on the Dhaka University campus. One afternoon I met up with Kumar Murshid who was in Class Nine. He lived in Dhaka University faculty housing. We began talking about launching a campaign inside our own school. The movement at the university was led by a central action committee formed by various student organizations. Kumar and I decided to launch our own action committee. We drafted a leaflet with nine demands, wrote up an introduction, and gave it a headline “Awake!” We ordered copies from a printing press on Central Road. We considered openly distributing the flyers ourselves, but in the end we chickened out. Instead, we just surreptitiously left copies at several spots around the school building.

Our demands included: 1) A student union; 2) Abolition of the hall monitor system; 3) Reduction of tuition fees; 4) Scholarships for poor students; 5) Increasing teacher salaries; 6) Freedom of press for the student newspaper; 7) Reduction in the rent of the canteen. Kumar and I had put together the list after talking to fellow students, a few of the lay teachers told us how poorly they were paid, and the man who ran the canteen had complained his rent had been raised. The hall monitor system was widely hated; Class Ten boys were chosen as prefects and lorded it over other students with power to give out detentions.

During the last class period of the day, one of the Brothers came to our classroom, and he also went to Class Nine and the two sections of Class Eight. He announced that they wanted to meet with representatives of the Josephite Action Committee on the weekend.

We were excited and scared. After school, Kumar and I met with other students we’d brought into our circle. We debated whether to attend the meeting with the Brothers. Some worried it was a trap, fearing they would learn our names and expel us. But most agreed that the time had come to step out into the open. We were no doubt encouraged by the fact that the mass movement in the country had grown stronger and by this time the Agartala Conspiracy Case prisoners, including Sheikh Mujib, had been released. We felt the backing of invisible multitudes behind us. We chose a delegation.

When it was time for the meeting, I showed up for Class Ten, Nine brought Kumar and Enayet, and Eight brought three or four whose names I don’t remember. The Class Eight boys surprised us with their eagerness and spirit. We all sat in the headmaster’s office facing two Brothers from the administration.

They went on the offensive. Why did we say ‘demands’? Wasn’t that hostile and rude? We argued that since there was no mechanism for students to express their wishes, demands made sense. But fine, we conceded, call them proposals. With this concession, they wore us down. They claimed teachers’ salaries were fair. They flatly denied the canteen rent had been raised; later we’d ask the canteen man again and he would reaffirm that it had been raised. They made some vague promises but the only concrete one was that they would allow Class Ten to elect a committee to consider changes in the monitor system.

In the aftermath, they did follow through with the committee. Since most of my class were monitors, they simply elected their own people. Nothing would come from that committee other than some promise that the monitors would act less rude. I can’t remember now but it is possible the Brothers backed down on the canteen rent increase.

As editor of The Sentinel, I wrote a front-page story titled “Students Demand Changes.” Or did it say “Students Propose Changes,” I can’t recall. I had not taken the draft to the faculty advisor, and I had to accept detention for my insubordination.

On March 25, Ayub Khan resigned and General Yahya Khan seized power. Martial Law was reimposed, though elections were promised and the new regime made some concessions like a student discount on public buses.

The Brothers at St Joseph’s invited each of us in the Josephite Action Committee to private consultations. Their words were soft, but the implication was clear. They said, now the country was under Martial Law, you should watch yourselves and stop your agitation. This became the excuse to stop any further consideration of our demands.

I learned a valuable lesson about how low-level power sometimes interacts with state power. We were quite aware of the threat posed by Martial Law, but how would the state authorities know what was going on at our school? They could only know if our administration informed them. It left a bitter taste in my mouth and I felt betrayed. In my seven years at the school, I’d mostly had good relations with the Brothers but something broke at this point. I could live with them not acknowledging our concerns as valid, but they went further by throwing out a veiled threat against us. It felt very wrong that they would threaten young boys with state reprisal in a country where dissenters were routinely persecuted.

That was the end of the Josephite Action Committee. In a few more months I would graduate and leave St Joseph’s. I did have one last hurrah. In early 1970 at our annual graduation ceremony, I refused to follow dress traditions and didn’t wear shirt and tie (I didn’t own a suit); I came in pyjama-panjabi and chappals. And the valedictorian speech I gave, which I had refused to share with them beforehand, was not something they expected. I only remember the first sentence: “We did not get the education we deserved.”

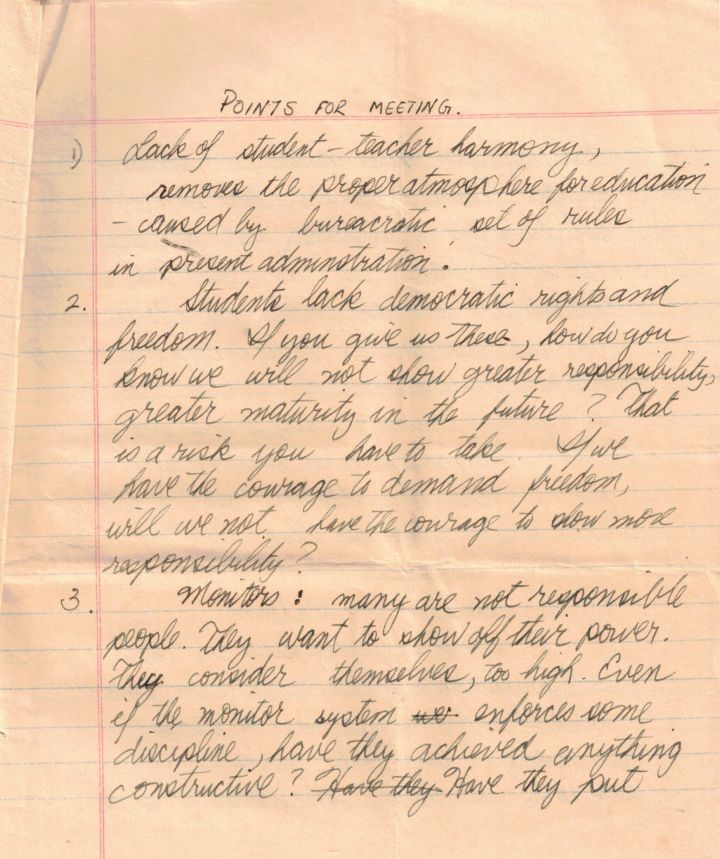

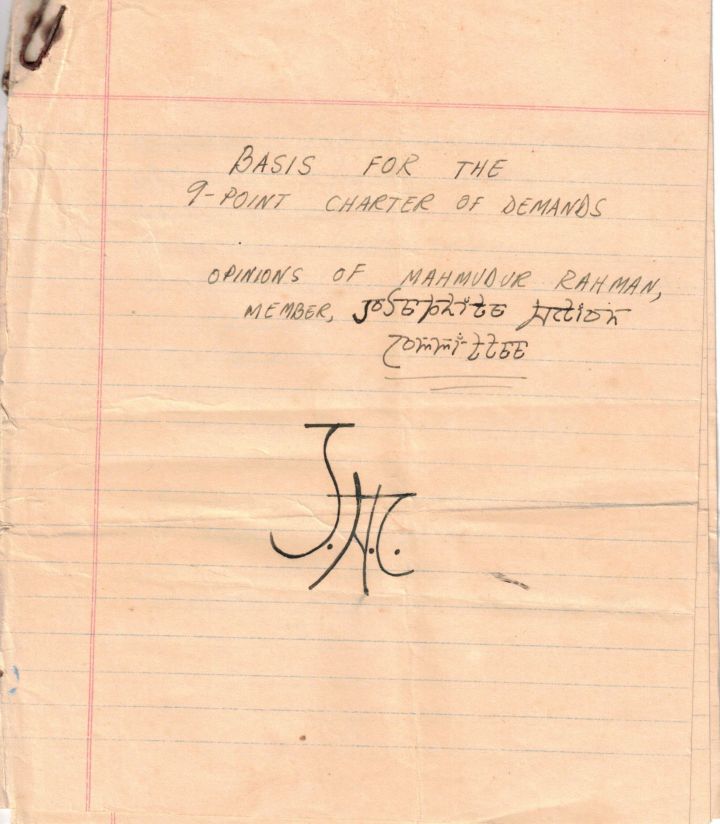

Some years ago, my brother Sani in Dhaka told me he found the speech. But he died before he could give it to me. When I was visiting in August, I couldn’t find it when I rummaged through his papers. I did find a small sheaf of notebook pages with a rusted paperclip holding them together. The cover page read, “Basis for the 9-point charter of demands: Opinions of Mahmudur Rahman, Member, Josephite Action Committee, JAC.” I have no memory of this document, but I must have written this up as talking points before our group met with the Brothers.

It’s fascinating to see what kinds of ideas were floating in my teenage mind. I seem to have been guided by notions of democracy, fairness, and justice. Much of that came from seeking to translate the spirit of the university student movements to our own school’s environment. There were other sources too.

The basic thrust of our demands was animated by notions of democracy. We argued for a student council for “ensuring democratic rights and to speak freely on all topics.” We sought freedom for the student press and “no curbs on protesting or moving about.”

In commenting on the hall monitor system, I seem to have been concerned both with the exercise of this petty power, the recruitment of students into mini-police, and how that corrupted my fellow students. I wrote: “Monitors: many are not responsible people. They want to show off their power. They consider themselves too high…. Most schools do not have this system and are they worse off than us? No! In those schools, students are not segregated into two sections. You are indirectly preaching segregation. These monitors are insulted, ridiculed, etc. It isn’t pleasing to come into school and see frowns & say farewell with frowns. Are you doing justice to them? You are turning them into machines, without feeling.”

We were also guided by notions of social justice, seeking to make a dent in the elitist nature of the school by making it possible for others who could not afford the tuition to attend. My notes observed: “1. School is English Medium; 2. School is monopolized by sons of aristocrats. These two facts have isolated us from remainder of student community. They think we have superiority complex, which some of us do.” I seem to have understood the value of class diversity, noting “Proper mixing of people of different classes to ensure development of children who will learn that the only world is not that in which they live.”

Similarly, we sought fairness for teachers and the canteen owner. About canteen rent, I wrote, “You have taught us to distinguish between right and wrong. Canteen rent too high is wrong. People who study in school pay a lot. Can’t you afford to do someone a good deed. Must you demand Rs 4 ½ per day?”

We were of course aware that the university students were demanding national political changes. I didn’t comment on that, but we did want the right to be able to participate in the national conversation. In my notes, I said, “You tell us not to indulge in politics. In present case, your country’s future, your future is involved. Don’t you have great stories of how children helped in the fight for Independence. Is it wrong to fight for your survival? So many have died, and if we do not condemn this, you are asking us to be devoid of human feeling.”

Indeed, this touches on how school children are galvanized to join in national movements. In 2024, when Hasina indiscriminately massacred hundreds of people, this feeling of empathy made schoolchildren join the movement. You have feelings, you empathize, you act.

In looking back at my notes, I was struck by two other things.

I argued from a notion of children’s rights, that children needed to be treated with care, as maturing adults. “‘The child is an individual in his own right and from birth should be so treated.’ You then provide him with self-respect. At same time, satisfaction with one’s self removes inhibitions. Self-confidence, once gained, provides a kind of security which helps make a person dare to live and with joy. A child’s moods must not be lightly ignored. If so, there is a break in self-respect. What the child needs is intelligent concern and a quiet, calm and friendly approach is the means.”

I argued against a punitive system, focusing on detention, the basic system of punishment. “Detention is all wrong. It teaches him nothing at all or almost nothing. Your investment of love, wise understanding guiding love is the best investment you can make. They come to you helpless, malleable and dependent on what you can provide. They leave you as men, the next generation, the blessed or the doomed.”

And though things were put in terms of demands and rights, the tone was not adversarial. The goal was to have better relations among students, with teachers, with the school. It seems that though the demand was for a student council to voice our concerns, I was open to the idea of a faculty-student council. I noted, “Lack of student-teacher harmony, removes the proper atmosphere for education—caused by bureaucratic set of rules in present administration.”

Looking back, decades later, I try to understand where these ideas of educational reform came from. Clearly the spirit was absorbed from the anti-dictatorship democratic movement; that led us to want a voice in our own immediate environment. Some of the ideas came from what we read at that time. One older brother had also brought some Unwin paperbacks and I remember reading Bertrand Russell and some other British socialists. In our home we got Time and Life magazines, and I was somewhat familiar with at least images, and perhaps some of the ideas, from the mass movements in the U.S. or other countries during the upheavals of 1968. At the very least I would have absorbed notions of fighting for rights and justice. Ideas about child rights in education probably came from Rabindranath Tagore. I remember encountering them in a translated collection of his writings that I’d borrowed from the British Council library.

Returning to the street art panel I saw outside Sunbeams school last year that insisted that political discussion was urgent and should not be banned, I wonder how students at that school interpreted the concept. Clearly school children participating in the movement against state murders and Hasina’s rule understood something of the national conversation. But beyond that? Sunbeams is an elite school and today, within a very stratified educational system in Bangladesh, there are more elite schools in Dhaka. Do students at such schools think about their elite situation? Do they see things in their schools that they decry? Do they look for fresh ideas about education and children’s rights? Do they consider acting on those ideas?

Appendix:

BASIS FOR THE 9-POINT CHARTER OF DEMANDS

OPINIONS OF MAHMUDUR RAHMAN, MEMBER, JOSEPHITE ACTION COMMITTEE

J.A.C.

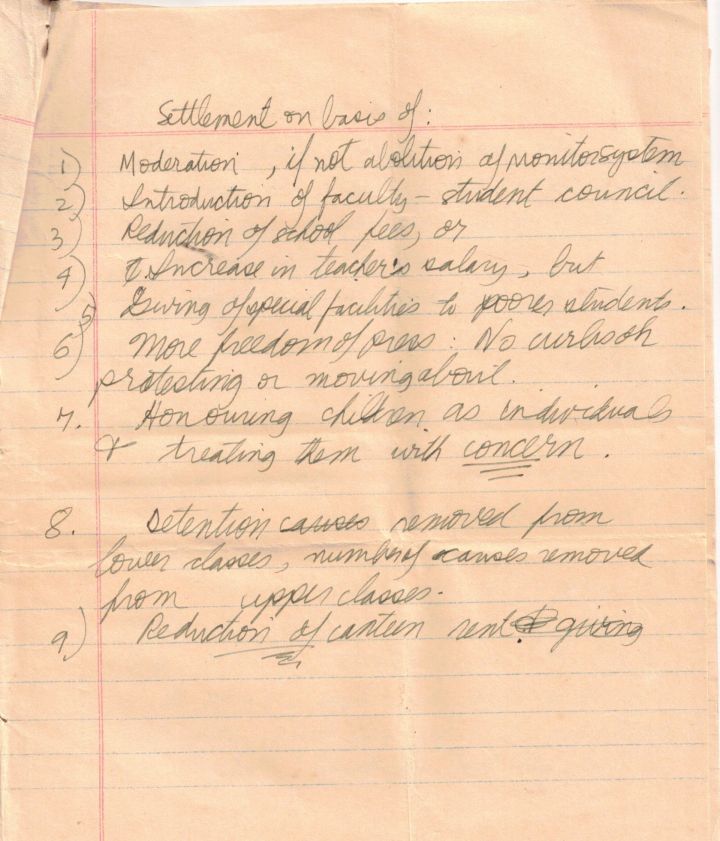

Settlement on basis of:

1) Moderation, if not abolition of monitor system

2) Introduction of faculty-student council

3) Reduction of school fees, or

4) Increase in teacher’s salary, but

5) Giving of special facilities to poorer students

6) More freedom of the press; No curbs on protesting or moving about

7) Honouring children as individuals & treating them with concern.

8) Detention removed from lower classes, number of causes removed from upper classes.

9) Reduction of canteen rent.

POINTS FOR MEETING

1) Lack of student-teacher harmony, removes the proper atmosphere for education – caused by bureaucratic set of rules in present administration.

2) Students lack democratic rights and freedom. If you give us these, how do you know we will not show greater responsibility, greater maturity in the future? That is a risk you have to take. If we have the courage to demand freedom, will we not have the courage to show more responsibility?

3) Monitors: many are not responsible people. They want to show off their power. They consider themselves, too high. Even if the monitor system enforces some discipline, have they achieved anything constructive? Have they put discipline in their minds. Most schools do not have this system and are they worse off than us? No! In those schools, students are not segregated into two sections. You are indirectly preaching segregation. These monitors are insulted, ridiculed, etc. It isn’t pleasing to come into school and see frowns & say farewell with frowns. Are you doing justice to them? You are turning them into machines, without feeling.

4) .

1. School is English Medium

2. School is monopolised by sons of aristocrats.

These two facts have isolated us from remainder of student community. They think we have superiority complex, which some of us do.

5) Student council needed for:

1. Maintaining good teacher-student harmony thus providing better atmosphere for education.

2. Ensuring democratic rights & to speak freely on all topics

3. Development of social values, to develop social usefulness.

4. Application of principles in books esp democratic principles.

5. Provide for an object of ‘fidelity’.

6. Relieving tensions between teacher-student.

7. Proper mixing of people ideas.

6) What kind of student council do we need?

1. One which relieves tensions between faculty and students

2. A faculty-student one in which students are informed of the world behind the doors

3. Run on highest principles of democracy

4. Majority and minority both to be respected

7) Proper mixing of people of different classes to ensure development of children who will learn that the only world is not that in which they live.

We can have one or two free students & several half free students.

Some students can help these with previous year’s books.

8) “Students cannot go near house.” Why not? Will they burn it up? If you did not have such restrictions, people would not take them on as challenges. Now they do. (You must build up a confidence in the students’ minds.)

You cannot write certain things about the administration in the Sentinel. You should not comment on the administration’s doings. You should not criticize teacher’s misbehaviour. You cannot protest against Headmaster’s decisions.

9) You think that the student is the one who is wrong in 9 out of 10 cases. State Rumman case if possible.

10) “The child is an individual in his own right and from birth should be so treated.” You then provide him with self-respect. At same time, satisfaction with one’s self removes inhibitions. Self-confidence, once gained, provides a kind of security which helps make a person dare to live and with joy. A child’s moods must not be lightly ignored. If so, there is a break in self-respect. What the child needs is intelligent concern and a quiet, calm and friendly approach is the means.

Detention is all wrong. It teaches him nothing at all or almost nothing.

Your investment of love, wise understanding guiding love is the best investment you can make. They come to you helpless, malleable and dependent on what you can provide. They leave you as men, the next generation, the blessed or the doomed.

11) You have taught us to distinguish between right and wrong. Canteen rent too high is wrong. People who study in school pay a lot. Can’t you afford to do someone a good deed. Must you demand Rs 4 ½ per day?

You tell us not to indulge in politics. In present case, your country’s future, your future is involved. Don’t you have great stories of how children helped in the fight for Independence. Is it wrong to fight for your survival? So many have died, and if we do not condemn this, you are asking us to be devoid of human feeling.