India sneezes, will we catch the cold?

By Jyoti Rahman for AlaloDulal.org

Just a year or so ago, the Indian economy was expected to be growing at a 8-9% pace, and people were talking about double digit growth into the 2020s. Within a year, growth has slowed to 4.4%, without there being any major shock —no financial crisis, no balance of payments crisis, no major natural disaster, nor any particular political tension. India just slowed, sharply. It’s now expected to grow only at around 4-5% a year, at least in the near term. Reflecting the slowdown, and the changed perception of India, the Indian rupee has taken a beating in recent weeks.

Of course, as with most things economic, it’s a bit more complicated than the above paragraphs, and there is no consensus on what exactly is ailing India, nor what the cures are, nor what the likely scenario is going forward. Here is a good summary that I find plausible. Here is the official story. Of course, there are other stories —Google if you are more curious.

This post is not about India as such, but how the ‘Indian crisis’ maybe affecting Bangladesh. Very short answer is a not-very-satisfactory ‘it depends’. Okay, a bit less short answer: if a full blown crisis is avoided in 2013, there may be upside for Bangladesh in 2014, but beyond that things become more complicated.

Long answer: over the fold.

——–

In the immediate term, a lot depends on whether India has a full blown crisis —by which I mean: India runs out of foreign exchange to pay for its imports or service its debt and has to be bailed out (by the IMF and/or others); and/or its economy slows even further with widespread corporate bankruptcy (including possible run on its banks) and job losses in ‘modern’ sectors of the economy.

If India were to have a full blown crisis, we might be victim of what is known as contagion.

After 9/11, turbaned Sikhs were victims of hate crimes in parts of the US. Contagion is the financial market equivalent of that. Basically, if India is in crisis, financial market —thwe wolves of Wall Street, the economic hit men —might look around the neighbourhood and see if anyone else can be taken out.

So, how much do we look like India?

The first place to look at it is current account deficit, which is a measure of how much a country is borrowing from the foreigners. Sometimes, current account deficit is actually a sign of a healthy economy —this is the case if foreigners are investing in the country because of its bright potentials. However, if a country is running a current account deficit, and its currency is plummeting, then it’s usually the case that the deficits reflect some underlying problem with the economy, and speculators are getting wise to the fact that the country has troubles.

This may well be the case with India right now. But as this chart (current account balance as percentage of GDP) shows, Bangladesh’s current account has been either in surplus or very modest deficit recently. So, by this traditional measure of crisis vulnerability, we are probably safe. Or at least, safer than India.

IND vs BD Current Account Balance as Percentage of GDP

Another traditional measure of vulnerability is stock of foreign debt. This chart shows that as a percentage of GDP. Bangladesh has reduced its debt quite markedly during the 2000s. But India isn’t a highly indebted country either. Neither countries have particularly high concentration of short term debt —one month of exports and remittance earnings can pay for existing stock of short term debt in both countries.

IND vs BD Foreign Debt as percentage of GDP

I guess there are two ways to think about it then —we are safe because we’re not highly indebted, but then again, if India is hit, how safe are we?

And that’s where another factor comes in. It’s not just the foreign economic hit men who can cause trouble. They can join a speculative attack after taka takes a tumble for some domestic reason. Consider a scenario such as this —a scandal ridden unpopular government is thrown out of office amidst political turmoil, and its cronies take sizeable amount of savings out of the country causing the taka to be devalued or depreciate.

Hypothetical?

This chart shows monthly percentage change in the dollar / taka exchange rate — if taka depreciates from 50 to 52.50 per dollar,that is a 5% ‘rise’, shown by a downward spike in this chart. Downward spikes are depreciation / devaluation here, got it?

Okay, now let’s look at when there have been such spikes over the past three decades.

US Dollar vs Taka Spikes

There was a big one in 1985, and another one in March 1990. These were driven by fiscal mismanagement of Ershad years. In both cases, devaluations were followed by structural adjustment packages by the IMF.

Then there was a period of prolonged instability in early 1991 —note this one, we’ll come back to it.

Then relative calm of the 1990s, with a few appreciations/revaluations even. But by the end of the 1990s, large devaluations became more frequent. Part of it was the aftermath of Asian crisis, when all currencies in the region lost ground against dollar. But by 2001, Asian crisis was a thing of the past, and yet we saw the largest devaluation in June 2001 —again, note the date.

Then relative calm for a few years, until big instabilities in 2005-06. Particularly note the spikes in late 2006.

After that, stability again for a few years, until a big depreciation in Jan 2012 followed by steady appreciation —this is when the rental plants came online, subsidies ballooned, the IMF loan came into play, and the economy stabilised.

So, some depreciations have clear economic stories, but three don’t. What are these three episodes? Early 1991, mid-2001 and late 2006. Now, my dear reader, what else do these periods have in common?

More pertinently, what might they have in common with the coming few months?

If there the taka starts sliding because people fearing political reprisal in Dhaka are buying houses in Toronto, will foreign speculators particularly care that Bangladesh has better ‘fundamentals’ than India?

And here is the scariest chart of this post, showing the number of months of imports that can be paid for by current stock of foreign reserves. It seems that we don’t look too much like India. No. We look worse! As of June 2013, our foreign reserves were enough to cover five months of imports. India’s would have covered eight. So, if India is in crisis and it engulfs us, we may be simply blown away.

IND VS BD Imports to be paid by Foreign Reserve

That said, there is no need to be particularly alarmist about these things. The IMF usually considers reserves worth three months of imports as sufficient. Both countries are safely above that. So, the chances are that there won’t really be any crisis —no Lehman moment. Chances are that Indian economy will settle into growth rate of 4-5%, and the rupee will settle at somewhere around 70 per dollar. And as for our political problems, well, we can always be hopeful that 2014 will start peacefully.

So, if we end this year without crisis, what could the new year hold?

Some good news, for the Bangladeshi consumers, and whoever is in power in early 2014, if the relationship depicted in the next chart continues to hold.

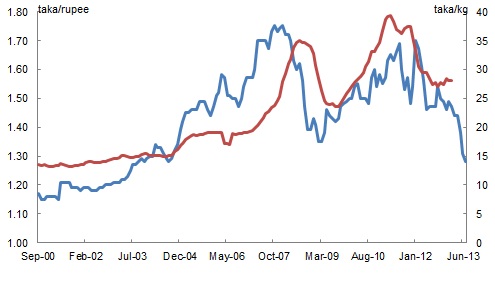

In this chart, the blue line plots the taka-rupee exchange rate against the left axis, and the retail price of a kg of coarse rice in Dhaka is the red line, which is against the right axis. There is a pretty strong correlation —when the taka slides against the rupee, rice prices in Dhaka rises, when the taka appreciates against the rupee, rice prices in Dhaka falls.

Taka Rupee exchange Rate and Rice Price in Dhaka

If the taka-rupee rate settles close to parity, all else equal, rice prices may well get close to that fabled 10 taka per kg —whether Hasina Wajed is around to reap political dividend is an entirely different matter.

Not just rice prices, if taka appreciates against the rupee for a long while, it will help the Bangladeshi consumers of Indian beef, onion, and other food products too. This would appear to be overall a beneficial outcome. But, and there is always a but in economics, any exchange rate realignment would also mean Bangladesh’s trade deficit with India will become wider.

Is this a problem? Arguably, no. In fact, arguably, the ‘we are becoming an Indian colony because of the trade deficit’ is really a political bogey man. Sceptic? Look at this chart showing Bangladesh’s trade deficit with India and China.

Bangladesh trade deficit with India and China

When was the last time you heard anyone worry about Bangladesh becoming an economic colony of China?

As we have seen above, Bangladesh does not have a current account problem. We may have trade deficits with India or China, but we have trade surpluses with other countries. So, overall, we have no external deficit problem. If the taka settles somewhere close to parity with the rupee, chances are that the trade deficit with India will widen as we buy more cheap Indian beef and onion. And I would argue that we should not at all be worried about that.

This is not to say that we don’t have a trade problem with India. We do. It’s just that we don’t have a trade deficit problem with India. The real trade problem we have with India is that the Indian market is closed to our products, including cultural products such as books or TV channels. And this problem reflects Indian politics more than anything else.

And that problem will likely to get worse if India finds itself in the slow lane. Whole generation of urban Indians have become used to the Rising Shining India mantra. They will find it harder to adjust to what was once called the ‘Hindu rate of growth’. And it is quite possible that they will take out their frustration at foreigners, including Bangladesh. We have already seen Bangladesh-bashing from Mamata Banerjee.

It could get much, much more shrill and ugly, particularly if there is a non-Awami League government in Dhaka.

What about beyond 2014?

In the longer term, India will need to tackle whole bunch of difficult policy issues. Normally, depreciation helps the exporters, but this may not be the case in India. Its politicians like to print money to win votes. It can’t even procure land to build factories. If it can resolve these, it will again grow fast. But the relevance for Bangladesh is not so much that India resolves them or not, but that many of these problems may well hold true for us. And ultimately, how we resolve our problems will matter far more than what happens in India.

(Data source for all charts: CEIC Asia).